Home > Building Background Knowledge

Monopoly in America

Snippet 1: John D. Rockefeller's Standard Oil Company, Monopoly in Action

The term monopoly describes a market situation where one seller controls the supply of a product or service and thereby inhibits competition.

Monopolies have an ancient history with two of the first being granted in ancient China, when China's Emperor gave out monopoly rights on salt and iron.

Like the Chinese Emperor, America's early industrialists also liked the idea of monopolies, none more so than John D. Rockefeller, the head of Standard Oil.

When Rockefeller founded Standard Oil in 1870, there were at least 250 other oil refineries.

Yet by 1878 Rockefeller had gained control of nearly 90 per cent of the oil refined in the United States.

His success was based on brains, hard work, luck, and what seems to have been a complete lack of conscience.

One of Rockefeller's favorite business maneuvers was to buy up or create oil-related companies, like the makers of tanks, barrels, and pipelines, and then jack up the prices for competing companies.

He would also secretly buy competing companies and then use officials from these companies to spy on the activities of competitors.

The sheer size of Standard Oil made it possible for Rockefeller to bully the railroads into granting him big rebates on shipping.

The rebates made his shipping costs much lower than that of any other competitor and worked to defeat the entry of new oil companies into the market.

The source of this paragraph is Ed Rosenthal, poet, broker, and economist; also this very interesting site, which focuses on Standard Oil and the federal government's long struggle to regulate it and other American monopolies.

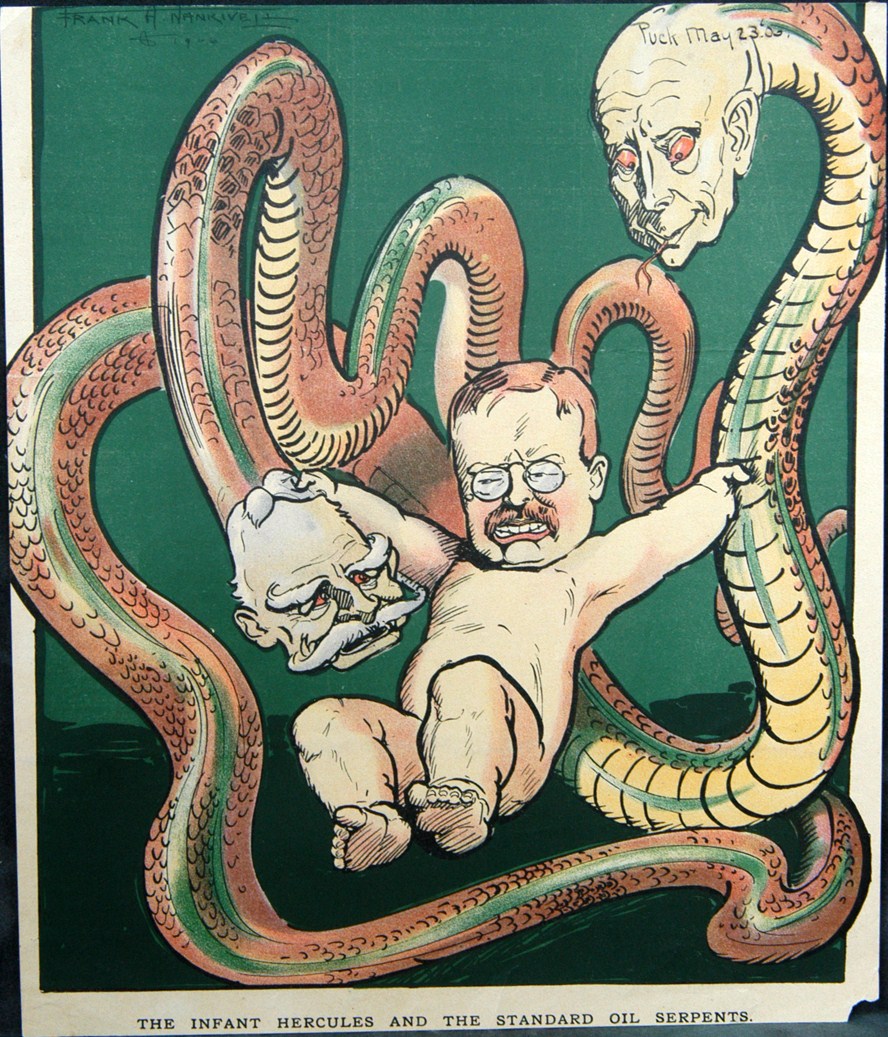

You can also go here to see a famous cartoon depicting Standard Oil as an octopus with other industries and congress already in its clutches as it reaches out for the White House.

For contrast, you can also find a defense of Rockefeller's tactics here.

I don't agree with the author's interpretation of the facts and events surrounding Rockefeller's practices or the public's reaction to them.

However, you should know that the point of view exists and you can evaluate it for yourself.

Snippet 2: Monopoly and the Muckrakers

"This corporation [Standard Oil] has driven into bankruptcy, or out of business, or into union with itself, all the petroleum refineries of the country except five in New York, and a few of little consequence in Western Pennsylvania....America has the proud satisfaction of having furnished the world with the greatest, wisest, and meanest monopoly known to history."

— Henry Lloyd Demarest, "The Story of a Great Monopoly" Atlantic Magazine, March 1881

As products like oil, steel and coal came under the control of single companies, many Americans became anxious about the lack of competition within the industries producing such essential products.

That anxiety was particularly high where Standard oil was concerned because no one was better than John D. Rockefeller at figuring out how to take and keep control of a market while squashing all competition.

In response to the public's fears, a number of investigative journalists began to delve into monopoly practices.

Among the first was Henry Demarest Lloyd who published his article, "The Story of a Great Monopoly" in 1881.

In the article, published in Atlantic Magazine, Demarest took on monopolies in general but focused, in particular, on the practices of Rockefeller's Standard Oil company.

Especially revealing is Demarest's account of how officers of the railroad and Standard Oil simply refused to respond to questions from state investigators because their answers might implicate them in criminal activity:

Just who the Standard Oil Company are, exactly what their capital is, and what are their relations to the railroads, nobody knows except in part.

Their officers refused to testify before the supreme court of Pennsylvania, the late New York Railroad Investigating Committee, and a committee of Congress.

The New York committee found there was nothing to be learned from them, and was compelled to confess its inability to ascertain as much as it desired to know 'of this mysterious organization, whose business and transactions are of such a character that its members declined giving a history or description, lest their testimony be used to convict them of crime.' "

But if state and federal committees couldn't gain traction when it came to their investigations, the same was not true of Ida Minerva Tarbell.

Tarbell was a journalist with firsthand experience of Rockefeller's tactics.

She had seen her father's wooden oil tank business destroyed by Rockefeller's expert use of "vertical integration."

He would buy companies at every stage in the oil production process, including the building of tanks, and then, for a while at least, undersell all his competitors until they folded.

Having personally witnessed the power of Standard Oil, Tarbell was determined to bring the oil giant down.

In particular, she was after John D. Rockefeller.

While Ida Tarbell certainly didn't destroy Rockefeller's empire—Ironically by the time Tarbell wrote, Rockefeller was the head of Standard Oil in name only.

He had retired in 1897—her nineteen-part series, "The History of the Standard Oil Company, " which ran between 1902 and 1904 in McClure's magazine, set the stage for President Theodore Roosevelt to break the stranglehold Standard Oil had on the industry.

Tarbell had done her homework carefully, and she detailed Rockefeller's tactics in a straight-forward way that left her reading public as furious as she was.

Public outrage was so great, Roosevelt had to respond forcefully.

However, he never forgave Tarbell, or investigative journalists like her, for their exposés of corruption.

He nicknamed them "muckrakers," claiming they liked nothing better than raking up society's dirt, while ignoring everything else positive.

Sources: For an altogether negative view of Rockefeller's business practices see Linux's information project. For a somewhat milder interpretation, see this PBS site.

Demarest's complete article is available here

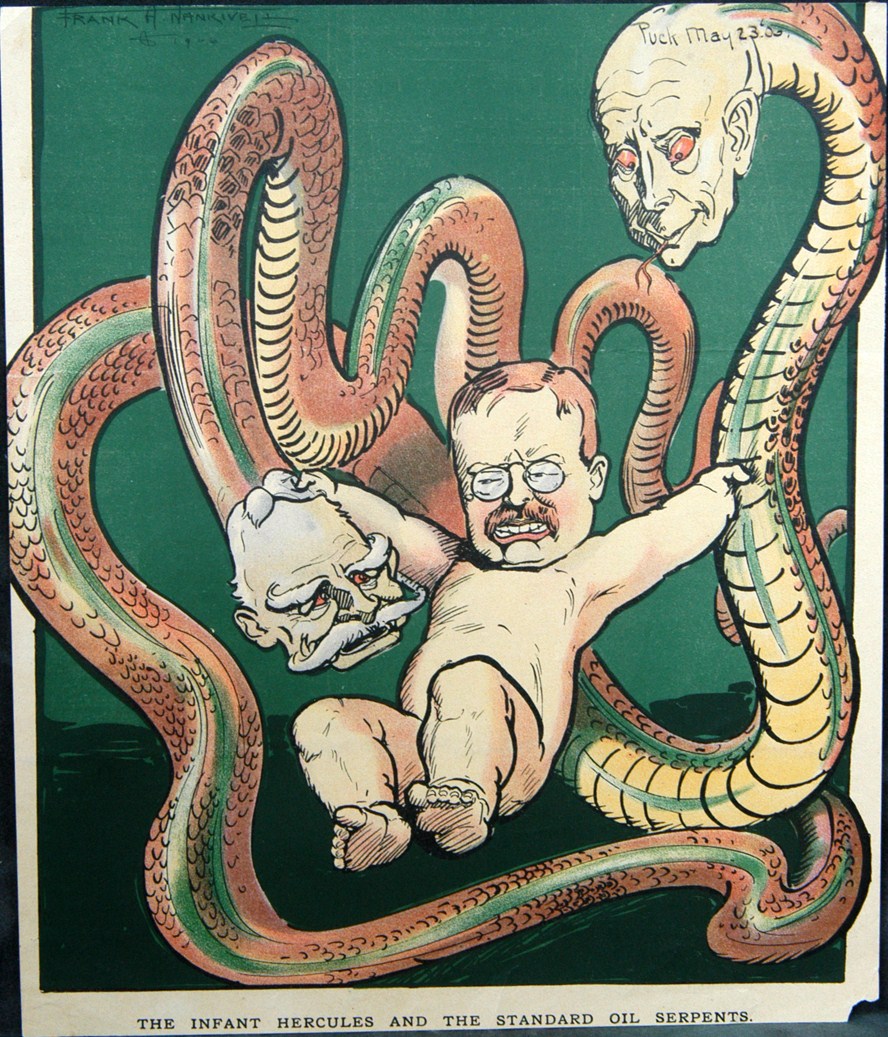

Snippet 3: Teddy Roosevelt, Trust Buster

|

Teddy Roosevelt in a 1906 cartoon captioned, "The infant Hercules and the Standard Oil Serpents" Source: Wiki Media

|

The Sherman AntiTrust Act of 1890 was the first Congressional measure that attempted to limit the growth of monopolies.

Its language was forceful and much less vague than its critics have claimed: "Every person who shall monopolize, or attempt to monopolize...any part of the trade or commerce among the several States, or with foreign nations, shall be deemed guilty of a felony."

Enforcement, however, was weak, despite the growing public outcry against the practices of monopolies in general and Standard Oil in particular.

Enforcement, however, got a lot tougher when Theodore Roosevelt became president in 1901.

In office when Tarbell's series was the talk of the nation, President Roosevelt, who would have preferred regulating rather than dismantling monopolies, was forced to take a hard stand or risk losing his reputation as a champion of political reform.*

Roosevelt rose to the occasion and took measures to limit the grip of monopolies on the country.

He persuaded Congress to establish a Department of Commerce and Labor.

Its job was to oversee interstate commercial transactions and monitor labor conditions of workers.

He also set up the Bureau of Corporations and instructed the bureau to make sure no corporation violated the Sherman Anti-Trust Act.

Perhaps most importantly, he set in motion 44 law suits against companies considered to be engaged in practices profitable for the country but harmful to U.S. society.

Among those companies was Standard Oil.

Even without Rockefeller at the helm, the company fought hard to maintain its control of the oil industry.

It wasn't until 1911 that the Supreme Court found in favor of the government and against Standard Oil.

Perhaps most importantly, the court set a precedent, or pattern for future cases to follow.

It issued in its decision, the "Rule of Reason," which said that monopolies in themselves are not necessarily bad and do not violate the Sherman Antitrust Act.

Instead, what the court considered illegal was Standard Oil's use of unethical tactics to gain and preserve control of the market.

As part of the ruling, the Supreme Court ordered the Standard Oil Trust to dismantle 33 of its most important affiliates and to distribute the stock to its own shareholders.

The 1911 decision paved the way for new companies like Gulf and Texaco to enter the industry.

It also paved the way for the discovery and exploitation of new petroleum deposits in Texas, suggesting that where monopolies weaken, innovation thrives.

|

Joseph R. Conlin, the author of the best American history textbook I have ever read,The American Past, offers an interesting comment from Roosevelt. It sheds some light on why he might have found investigative jouranlists like Tarbell and Demarest to be such nuisances:" How I wish I wasn't a reformer. Oh Senator